Chapter 4

Child of the River Spirit

1500 – 1535

The water was refreshing though warm from the late summer’s heat. It was the Moon of the Early Harvest, and I was full of baby, ready to give birth any moment. This would be my third birth. I knew what to do. My mother and sisters would be by my side to help me. I was not as fearful as I had once been.

My friends were bobbing with me above the middle of the riverbed when the first sharp pain struck; I felt my whole body quicken and go into action. I shouted to my friends and we rushed to shore as fast as we could swim, but I felt the baby slipping from between my legs! I screamed, and we all frantically dived to find the little one below the green water.

Feeling a small form brush against my leg I dove under to see my baby turn toward the river’s flow and move his tiny arms and legs just like a frog! I snatched him up and he gasped as he rose into the air! He wailed loudly like a fish might if it could when pulled from its water world. We were all amazed as we swam slowly to shore with my friends surrounding me and my baby so he would never slip from us again! From that day forward, we understood he belonged to the river spirit. And today, look at him. He is our tribe’s Navigator.

~~~

This is how my mother related my birth story, repeated from when I was young even until now, twenty summers later. I confess, I never tire of hearing it because it reminds me of my purpose. After I became old enough to accompany my brothers and father on river trips down to the Big Waters, I found that I understood the river better than anyone, but I do not know how or why. It is a gift from the creators I believe.

This is the red river of our origin. It can rage and then calm; it can be red, black, grey, green, or golden. In the Moon of the Melting Snow the river carries red swirling silt down into the valleys and low desert and outward to forested riverbanks, depositing it as water receded.

Below us the river meanders, twists and turns back on itself like a coiled snake. On it goes, breaking into many streams and bayous that spread out as far as we can see. Within its form are shallows and deeps, and places men disappear in soft mud. Near the big waters, the rice grows along the way. We dig up clams and abalone, net crabs and shrimp, and marvel again at the abundance of the world around us. We harvest with respect for the spirits who guard the land and water and fill all things with life. We net turtles from the Big Waters and roast their meat on the beaches. The multicolored sparks from driftwood gathered by children fill the sky above our fires, and we study the black sky and shimmering stars, long into the quiet night. We read the heavens and tell ancient stories from elders who passed them down from time immemorial. We sleep in deep restful bundles, our feet to the fire, until the morning sun awakens us, and the screech of the shorebirds picking through the remains of our evening meal makes us rise to chase them away.

We remain on the ocean and lower delta of the river for weeks, watching the river run itself out to sea. When we return upriver to our ancestral fields, our work begins to plant the seeds we have stored and to tend them to harvest.

I pole and probe the river bottom to determine the best routes for my people. Like a game, it changes with each season, challenging me to observe its moods in currents, speed, and colors. As we pole on rafts to the sea, I watch for deer people, the otter tribe, and clans of feathered ducks in every shape and color. I collect the feathers dropped in my path, and I give thanks for the swimmers, crawlers, and stalkers that are also my family. We watch for the mountain lion and jaguar that come into these wooded paths along the river to hunt the same game we seek. We are stalkers all.

My days are spent in this way, but when the cold season comes, and the river is resting, I find quiet rest inside our hut with the fire reaching toward the smoke-hole, and all of us making something with our hands and telling stories to entertain us.

Until my mother joined her family on the other side, I always heard the story of my birth. I am the Navigator of my tribe.

In a far distant time …

Albert Pope was already on the river in the cool of the morning having launched his small fishing boat in the gray dawn. He allowed the slow current to carry him south, past the RV park with its trailer city. The gauzy traces of last night’s moon lingered above the horizon. Albert had spent the night outside of his own trailer on the rez. He’d told stories to his family and neighbors about the old times until one by one they each disappeared to lay their heads upon a pillow and dream. Albert had stayed up all night, watching the golden moon’s light illuminate the sky while he listened to the desert’s nocturnal creatures flit and scurry about. Going fishing was a natural extension of night to day.

Albert sat in quiet contemplation watching where his fishing line cut into the green water. He focused on the wedge-shaped pattern on the surface where his line plunged down. A quiet man in his late sixties, Albert had outlived most of his peers. The average lifespan of tribal men was only forty-eight years. Diabetes, alcoholism, and heart problems took them before their time. Albert had quietly watched as generations of Yuman men gave in to depression and anger—turning to alcohol or drugs— to dampen the pain of living in two worlds.

Suddenly his concentration was broken by a strong tug on the line. He pulled back reflexively. The fish went wild beneath the boat. Leaning forward, he peered into the opaque water where he glimpsed a brief movement—a pinkish-gray flank illuminated by the soft light of the rising sun. He held the line taut, reeling it in slow and steady. Beads of sweat rolled down his forehead from where his broad Stetson hat met his dark skin. Finally, he lifted a large tilapia out of its watery world. It twisted and turned in protest, eyeing him as it flapped its tail hard on the boat’s aluminum shell. Albert removed the hook from the fish’s thick lower jaw. For a trash feeder, the tilapia was a beautiful creature, he thought. It briefly glimmered in rainbow colors before the air dimmed its radiance. He thanked the fish and tossed it into a five-gallon bucket to join its ill-fated cousins. Then, he prepared another line to set out.

Albert felt a great deal of satisfaction that he could still feed himself and his neighbors. Drifting downriver, he thought about the stories his elders had told about the river, how it once ran red and wild, chockful of six-foot salmon “so numerous you could walk across the river on their backs.” He had long imagined the wildlife, thick forests and gardens that once lined the riverbanks. He felt a pang of sadness that long ago hardened into a permanent knot in his center, a steely resistance to a lifetime of mourning the demise of his people and a once-great river. Yet both persisted, outcome uncertain.

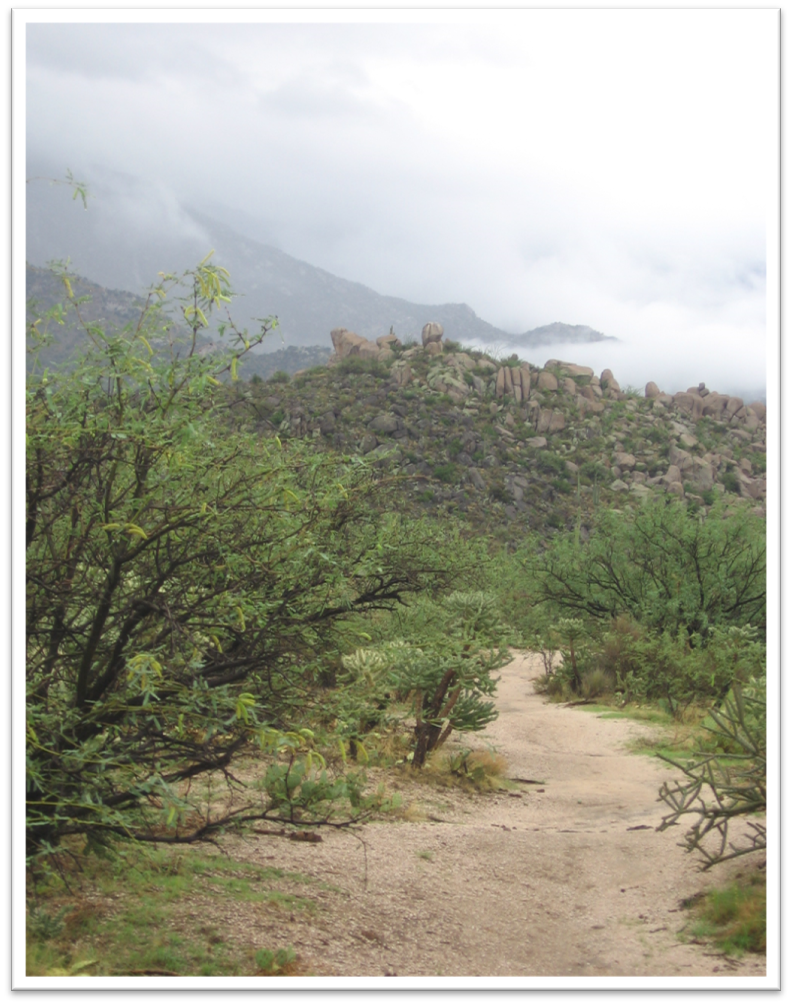

Lower Colorado River as it meanders to the great delta and the Sea of Cortez.