Tag: Fiction

Dreaming a New World

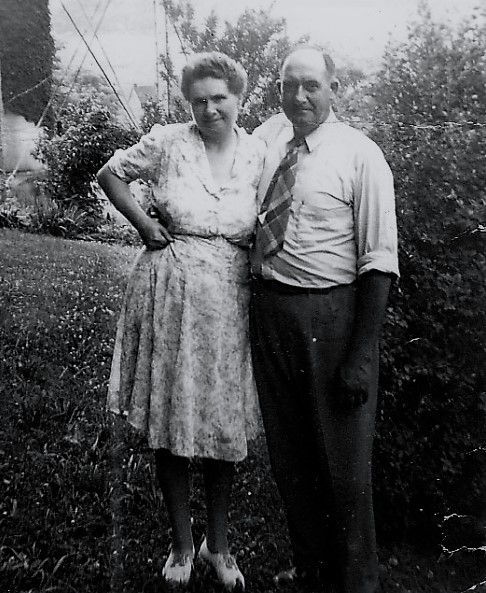

Below is the dedication of my first novel, Threshold, in which I give credit to my grandparents for sparking the idea to write a novel of hope and possibilities.

Steinbeck and Erdrich

For man, unlike any other thing organic or inorganic in the universe, grows beyond his work, walks up the stairs of his concepts, emerges ahead of his accomplishments. ~ The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck. Goodreads.

John Steinbeck’s conviction that latent capacities lie in wait of the challenges we may face is the power of his stories. Steinbeck was a man with his boots set firmly in his homeland: the San Joaquin Valley. He wrote about migrant labor, loss of natural landscapes to industrial scale farming, and poverty created by the concentration of wealth by a few. He sought to understand ecology when he sailed with his biologist friend, Ed Ricketts, to study the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California). In The Log of the Sea of Cortez, he and Ricketts articulate how life works in linked communities which predated more contemporary scientific understanding of ecology by decades. I highly recommend this book to Steinbeck readers to understand his curiosity and breadth of knowledge.

In recalling The Log’s philosophy, I am struck with how Louise Erdrich not only comprehends the interrelatedness of all life, but she also found her understanding in the places she grew up: the Red River Valley where the Red River flows north toward Winnipeg from Fargo, North Dakota. Today it is a highly engineered river to meet human and industry needs, but once it ran free, annually flooding its banks in the spring runoff to nourish the valley’s soil into rich black loam yards deep. The story that Louise tells in her recent acclaimed novel, The Mighty Red, is centered in this valley among families beginning in 2008 when an economic collapse stressed working families many of whom lost property and/or became homeless overnight.. Some work in the industrial beet operations, others are rich landowners who have bought out small family farms. Another family is working to improve their land in the old way, come what way may. They preserve native “weeds” and regenerate soil.

Something Louise Erdrich has mastered is THE WEAVE – my concept for threading people’s stories in the geography of place. Louise’s mother is an Ojibwe elder in the Turtle Mountain Band of the Chippewa Tribe. Her grandfather, Patrick Gourneau, saved their reservation from the U.S. government’s veiled attempt to take land designated to their tribe by treaties to allow wholesale taking of forests and minerals (Termination under the guise of Emancipation). She told this story in her novel The Night Watchman which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2020. Storytelling is in her blood as this was a primary method of recording history and imparting values, and cultural and spiritual practices among her people.

Louise Erdrich inhabits a pantheon of great writers who possess piercing insight into contemporary American culture and politics. For Louise, her ready access to indigenous ways of knowing lends the power of truth unadorned but artful. It’s a combination that has drawn a worldwide readership.

Like Steinbeck, she builds stories from decades of lived experience in a particular geography – what Gary Nabhan termed the geography of childhood.

Erdrich is imbued with a wicked humor, gift of elders in her tribe voiced through her unforgettable characters with names like Happy Freshette and Father Flirty. But don’t be fooled that her writing is entertaining in the normal way we might think of a western cowboy genre. Erdrich’s gift is alchemy. The impact is more than its elements. At the end of every book I am better than I began. She has gently led me to reconsider the human condition through her characters, to see it in fine definition, beautiful and tragic, heroic and funny.

I’ve laughed and cried my way through the lives of her characters and come to love the places where their destinies unfold. In The Mighty Red, Crystal and Kismet, Hugo and Gary, are caught up in a teenage love triangle and a mother’s quest to protect her daughter. The geography of place includes the beet farms producing sugar (a poison) while “weeds” are eradicated by an unrelenting war on native plants some of which are highly nutritious, she shows readers the profound irony of modern culture’s misunderstanding of the land under its feet. She brilliantly shows readers the interconnectedness of life, artfully described as the “joinery of nature.”

As she approaches 70, Erdrich is more powerful a writer than a decade ago. Winner of the Pulitzer, the National Book Award (twice) and hundreds of other awards and nominations, she has left America and the world a treasure of stories that speak the truth while encouraging us all about our frailty in the face of uncontrollable forces. Yet, even then, like her grandfather, we ‘grow beyond our work, walk up the stairs of our concepts, and come out ahead of our accomplishments.’

I await her nomination for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

A Reading Life

“A reader lives a thousand lives before [s]he dies . . . The [hu]man who never reads lives only one.” ~ George R.R. Martin

Readers of this blog know that nature is a constant theme in my writing, reading and public work. We all have our roots plunged in soil we call home as did Lauren Groff, a magnificent writer who first found her inspiration at the family farm in New Hampshire.

Groff’s recent novels The Vaster Wilds and Matrix. pose profound questions about how religious and cultural practices have led to the depletion of nature’s resilience and how both men and women contribute to it when acting from an anthropocentric view. The journeys of discovery of both female protangonists is personal, imbued with hopes and dreams in the crucible of living their lives in times when women possess little social agency.

Groff is currently writing the third in the “triptych” of stories that carry the thread of inquiry and discovery. Readers are led to consider our present predicament of killing the very thing that gives us life: the living Earth.

Here are two excellent interviews that explore how Lauren Groff came to write each story, all the complex threads of thought, stories and influences that helped her conceive these outstanding novels.

The first interview explores The Vaster Wilds which takes place briefly in Jamestown colony in the “starving time”and mostly in the American wilds in 1609 North America.

The Matrix concerns Marie de France, the first published female poet in France, a poet and deep thinker whose writings are surprisingly free of social and religious strictures on women at a time of low female agency. Many sources contributed to the final story Groff tells. I found this instructive and supportive for writers of fiction.

This lecture from the University of Notre Dame is in my view the best exploration of how Matrix evolved and the exceptional thinking of one of America’s most brilliant writers of our time.

As a writer who shares the theme of nature I am so grateful to Lauren Groff for demonstrating the power of fiction to move us to understand the deep roots of our misunderstanding.

A book of rare beauty

About a decade ago I put together seven book reviews of a group of novels with related themes. Seven Stories was never published except on this blog.

The book that inspired me to begin this project is The Loon Feather, Iola Fuller, published in 1940. Here is the pdf of that synopsis. The author shares a great love of the land and the original people. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings reviewed it as a book “of the rarest beauty”.

I believe the authors in the Seven Stories collection bring readers a certain kind of wisdom we sorely need now. Start with The Loon Feather located on Mackinac Island in the Great Lakes.

Unsheltered – Barbara Kingsolver

With authors I value, like Barbara Kingsolver, the wait for a new work can often be lengthy. My wait was amply rewarded. In Unsheltered–2018 HarperCollins–she had created parallel narratives that articulate across two centuries in the American experience. Her device is a house and property shared by the characters in different centuries. The 21st Century Wilma and 19th Century Thatcher are adults navigating giant shifts in social paradigms. For Wilma and her family it is the economic collapse of the middle class and the dissolution of the ideals her generation pursued. Climate change knocks ominously at her door. For Thatcher it a pre-Darwin American culture in a panic to hold onto Christian perspectives by rejecting rational observation of how the world works (akin to today’s denial of science).

With authors I value, like Barbara Kingsolver, the wait for a new work can often be lengthy. My wait was amply rewarded. In Unsheltered–2018 HarperCollins–she had created parallel narratives that articulate across two centuries in the American experience. Her device is a house and property shared by the characters in different centuries. The 21st Century Wilma and 19th Century Thatcher are adults navigating giant shifts in social paradigms. For Wilma and her family it is the economic collapse of the middle class and the dissolution of the ideals her generation pursued. Climate change knocks ominously at her door. For Thatcher it a pre-Darwin American culture in a panic to hold onto Christian perspectives by rejecting rational observation of how the world works (akin to today’s denial of science).

Wilma’s multigenerational family reflects at once a 1) disenfranchised, racist white America (grandfather); 2) boomer parents (Wilma and Iano); 3) grown kids who pursued differing paths–Harvard financial education (Zeke), and post-apocalyptic youth (Tig). Add Baby Dusty, Wilma’s grandson whom she is mothering after the death of Zeke’s wife, and you have four generations, each navigating their own realities. The dialogue along the way explores the contemporary ocean of conflicting values and ideas of today’s American society with our economic, social, and environmental challenges.

Unsheltered is a nuanced conversation between Kingsolver, her characters, and the reader that is slow at times but never boring and long enough to examine previous and contemporary times for understanding the confabulations of collective memory–an existential wail of ‘Who are we?’

Twenty-something Tig exclaims to her mother, “The guys in charge of everything right now are so old. They really are, Mom. Older than you. They figured out the meaning of life in, I guess, the nineteen fifties and sixties. When it looked like there would always be plenty of everything. And they’re still applying that to now. It’s just so ridiculous.”

For individuals like me, awash in Trump-a-Con, Unsheltered is a beacon. Kinsolver’s Afterward explains her own journey to understand “the times”, explaining to readers how she wrote a novel about real historical figures and set the novel in South Jersey in a small town, Vineland. Along the way, she traveled many miles, including London where walked in the footsteps of Charles Darwin.

This book is a needed contribution to understanding our time as one when the “world as we know it” appears to be ending. It is ultimately a great story that takes us into the author’s creative mind. I am so grateful to Kingsolver!