Ancient Songs

I learned more about David Tejano on this trip. We met again at The Crossing restaurant. David brought his wife, Sharon, and their three children who were 8, 10 and 14. I learned that David worked a 14-hour day as one of three social workers. I observed some friction between David and his wife in their exchanges about his busy life. Sharon explained that David was a spiritual leader as well, a Bird Singer, and he participated on several committees.

The kids were quiet but lively. I told Sharon about my job at the university as an environmental educator, and how I hoped that we could organize an interesting project for youth. The older boys made suggestions, mostly about sports, and the youngest, a girl, wanted to do an art project. I was glad to see that at least children thought it was a good idea.

We ordered. David went for the fried foods again for which Sharon admonished him and patted his round stomach. Later he slathered butter on his corn tortillas as Sharon looked on and he laughed.

“So, I managed to get a small grant for whatever project the River People may wish to do,” I said, changing the subject.

David nodded approval and said that would be good for the meeting with the elders, to show we had some skin in the game. I marveled at his use of language and how he seamlessly managed the two worlds he navigated with apparent ease.

“Do you know what the elders have in mind?” I asked.

“Not a clue. They don’t share much with me either.”

I laughed. “That makes me feel better.” Sharon smiled in recognition of my position. David had filled her in on the Tribal Chairperson’s welcome.

“That was brave,” she said.

“Self-defense, I believe!” I said.

“You were honest. That goes a long way among our people.”

David filled me in on where to meet him as we parted ways. I took a carton of flan back to the hotel. That had to be the best dessert in the world. A caramel custard to rival my mother’s egg custard. I was feeling more comfortable in Yuma and with the idea that I might be able to establish a lasting relationship with this amazing nation of people. They were still present, and they were reviving their cultural traditions. But much had been lost.

~~~

I met David at his office. It was the first time I noticed how many people, mostly men, were in wheelchairs . . . amputees from advanced diabetes. They stared right through me or did not look anywhere at all. I felt very uncomfortable there in the waiting room of his building. The weight of what has happened here is manifest in these people, sick and depressed about their conditions.

David greeted me about ten minutes late and apologized. By my demeanor, it must have registered how difficult that time had been for me. I could not shake a profound sense of guilt.

“Don’t go down taking the sins of the fathers upon you,” he said as we walked down a long hallway into the sunlight at the back entrance.

“I can’t help it. Our policies, our theft . . . I am struggling with it.”

“Well, then do something about it. It’s not like it’s over,” he bluntly stated. I looked up at him and saw that he was smiling.

“I guess that’s why I am here, though I am not sure how a little environmental education program can make a difference.”

“You might be surprised. Some things get done by just continuing to show up.” David was wise beyond his years.

~~~

I was pleasantly surprised to join the museum director and elders at the new cultural center. It was small but beautiful, featuring the art of the River People and their history and material culture: clothing, fishing and hunting implements, war clubs, and many other everyday objects from times past. The director was a tall stately woman dressed impeccably in a long flowing skirt and jacket top, with dramatic makeup and jewelry. Her long dark hair was pulled back on both sides with beaded hairpins. She looked almost Asian, with very pale skin and watery grey eyes. Her assistants, though younger, presented themselves as grandly as their director. A breakfast buffet with coffee and juice had been prepared. Compared to my last meeting with the elders, this felt closer to how I greet guests at our offices in Tempe. However, later I was told by the director that the cultural center and museum always prepare a lavish spread for the elders. That was a reality check. This was for them, not me.

David left me there to mingle in the all-women gathering. He said he would return at noon. I would miss his supporting presence. I gulped and joined the group. I felt too casually dressed compared with the museum crew. My culture’s ways of relating were varied, and my workplace had gone casual. For a moment, I wondered if I should upgrade how we do things in the almost all male Southwest Center. As a daughter of a military officer, my mother had taught her girls how to dress to show respect, but then the women’s liberation movement shattered that tradition. The culture of casual dress at the University sealed the deal. I made a mental note to clean up my act on the next visit.

Marion, the director, introduced me to her assistants and then invited the elders to the table, suggesting her assistant could also bring them a plate if they preferred. I waited with her as the elders were served; then she indicated I should go next. After we all had our plates and beverages and returned to our seats, which were arranged in a circle, we simply ate in silence with an occasional comment from someone about the food, or an observation about the beautiful morning, and so on. It was an old fashioned social meeting among women. I had not been in on a scene like that since sorority days in college with tiny sandwiches, frosted demi-cakes, and punch.

After everyone finished and the plates were collected, we began a formal meeting with the elders. Marion led the way.

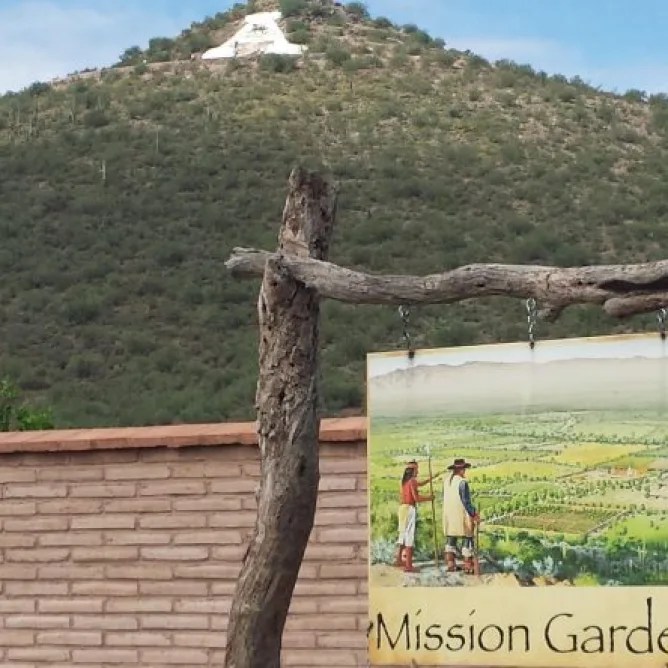

“The elders have discussed the idea of a project for youth. They think it might work well if the children learn something about gardening in the old way and then learn the names of the traditional plants and farming practices. It could also be a way to add to the language recovery efforts.” She paused and looked among the elders to make sure she was communicating what they intended. “Do any of our elders wish to comment?” she asked.

A woman named Georgina spoke up. She had wavy, graying hair, shoulder length, fleshy cheeks with many wrinkles, and dark merry eyes. She was rotund and wore a flowing rose-patterned dress over her large bosom and belly. She was wearing support hose and heavy black orthopedic shoes. Her ears were adorned with long shimmering pink and white beaded earrings.

“Back when I was a little girl, we still farmed in the mud of the river after the flood was finished. The seeds we planted are the old ones, the ones that grow well here.” She pointed toward the landscape visible through the large glass windows in the meeting space. “Most of our kids today have neither seen nor tasted the native melons, beans, and greens that were all we had to eat back then. I think that kids could grow some of these old ones in a garden near the museum.” She looked over at Marion.

Marion was quiet for a while. Another elder spoke up. “It will be a challenge to interest the teens; they are too far into the modern culture to care. But the little guys might want to do it.”

We sat in silence while thinking about this idea, to start with much younger members of the nation.

Another elder spoke. “Teens are lost, you know. Many are already showing negative attitudes.” She was a little younger than the other elders, slim by comparison, with beautiful hands, Vicky noticed. “I am thinking we should ask them to help the little guys. Give them a leadership role. They will learn along with the kids. Saves face.”

That made the women giggle.

“Miss Greenway, do you think the university would support such a project?” Marion asked.

“Yes. I think it fits very well with the intent of the center,” I said. “Learning the native plants is directly connected to land and water and will be a wonderful, fun . . . a delicious way for children to learn at the same time.” Then I decided to announce that the center had agreed to invest $5,000 in this project. “That should be enough to buy whatever you may need and have some money left over to support the ideas the kids may come up with.”

There were murmured comments among the elders. Marion cautioned it would only be successful if kids wanted to do it. She suggested that the project be based in the museum programs and that the museum staff manage the money. The elders and Marion had already determined a place for a garden in their original blueprints for the museum.

That seemed to be a good way to implement it, so I agreed.