A novel by Susan L. Feathers, Copyrighted 2021

Chapter 3

Not a Drop of Water

Bill Sherwood was a lanky man who impressed me by his warmth. His rounded shoulders spoke of the heavy load he had carried in defending wild places from development, and perhaps his own personal struggles, whatever they may have been. His light brown hair fell in straight locks across his forehead, shading his eyes. He seemed like a kind grandfather figure to me.

Bill took a lot of time to help me understand potential issues that might be part of an environmental education program. I appreciated his earnest effort but was dazed by the time our two-hour meeting came to an end. I tried to review what I thought I’d heard as he listened keenly.

“Okay. Basically, there is no Colorado River water that flows past the River People’s reservations. They are high and dry. Most of their land is leased out to farmers who buy allotments of Colorado River water to divert it via canals to the farmlands for their crops. Correct?”

“Yup, that’s about it.”

“And, the natural communities of mesquites, willows, and cottonwoods are gone except for scattered communities where the water table is high enough to support growth. The River People have planted tamarisk trees that are fast growing in those places, right?”

“Yes, there is a great need for these trees because the tribe’s traditional ceremonies for their departed—cremation and other related ceremonies– require a constant source of firewood,” Bill affirmed. “But that is only a small part of why the old forests were necessary. Those forests, they are called bosques or woodlands, harbored abundant wildlife that fed the tribe, drew water up from the water table, and provided medicinal substances that kept the River People healthy. The worst part is that the River People helped harvest that wood to fuel the steamboats used by the U.S. Army and ambitious businessmen to ferry supplies and people across or up the river to support settlers moving westward. The River People were hired as steamboat pilots because they knew the river better than anyone. They were paid in beads, later in coin. Their way of life began to transform like the forested land along the river.”

I reviewed my notes. An uncanny silence filled the space of Sherwood’s office as I took in the information. We both felt the weight of knowledge about our own culture’s impact on the River People we now came to serve.

“Bill, it is not at all clear to me how a little environmental education project will have any impact on these matters. In fact, it now feels trivial. What’s your sense of it?”

He stood up and moved to the window behind his desk. Bill was lanky and skinny as a rail except for an old-age paunch around his waist. He possessed a sculpted, long-jowl face, the kind illustrators love to sketch.

“You know, it might actually be just the thing needed.” He turned toward me to finish the thought. “Kids need to know what was lost and be a part of bringing it back, at least to some modern form of the natural habitat. Restoration can be healing for those who participate.

~~~

Leaving Bill to his work, I walked over to the Cultural Center. Inside, a small but exquisite gift shop exhibited the beadwork of Cocopah artists—multicolored yolks in geometric patterns. A young woman in a cobalt blue blouse and white skirt was wearing one of the yolks in patterns of white, yellow and red beads. Against the darker cloth, it was striking. Her long black hair hung in waves, held back on one side by a matching beaded clasp.

She greeted me warmly. “Welcome. Are you looking for something special?” she asked. In contrast to her impeccable appearance, including heavy eye make-up and ruby red lipstick, I suddenly felt very plain.

“Well, no. But…yes!” I suddenly remembered the upcoming university graduation party I’d been invited to. “I have a silver top and black skirt that one of these necklaces would truly enhance. What would you recommend?”

“These are yolks, a traditional form of adornment that our women invented when we began to trade with foreigners. I think they may also have been inspired by the yolks from pioneer women’s dresses. How about this one?” She held up a yolk comprised of iridescent red beads with geometric patterns of black and white beads. She came out from around the counter to help me put it on in front of a mirror. It was the most beautiful beadwork I’d ever seen.

“Yes, this will be dramatic against the silvery top. Thank you,” I said. “How much does it cost?”

From behind the case again, she checked the tag, and said, “This one is by one of our best artists, an elder. She is asking $500 for it.” She looked up to see my face probably go a little pale. She smiled and explained that hundreds of hours go into the making of the yoke.

“Then, I will wear it with pride. Yes, please wrap it for me; I am traveling and do not want to damage it.” I figured it was one of those moments, like the meeting with David, when two nations converge. Investing in an elder, in the traditional arts of the River People seemed the right thing to do. Besides, I had squirreled away money for a vacation and this seemed like a good use for it.

The young woman’s name was Sabrina Johnston. Her comportment communicated humility blended with self-confidence. The River People were not a weak nation. They had withstood an onslaught of injustices. Yet here they were. It was good to see and made me feel even more confused about the assignment I’d been given. Just who needs the help? I wondered to myself.

On a bookstand in the small gift store, I found a history that Sabrina affirmed was the one everyone trusted as correctly describing their lineage, language, traditions, and art. It was a book written by a nonnative woman affiliated with the state university, which encouraged me in my thinking that relationships could be built from trust and a good intent.

But that thought turned to ashes at the Tribal Council meeting some days later.

~~~

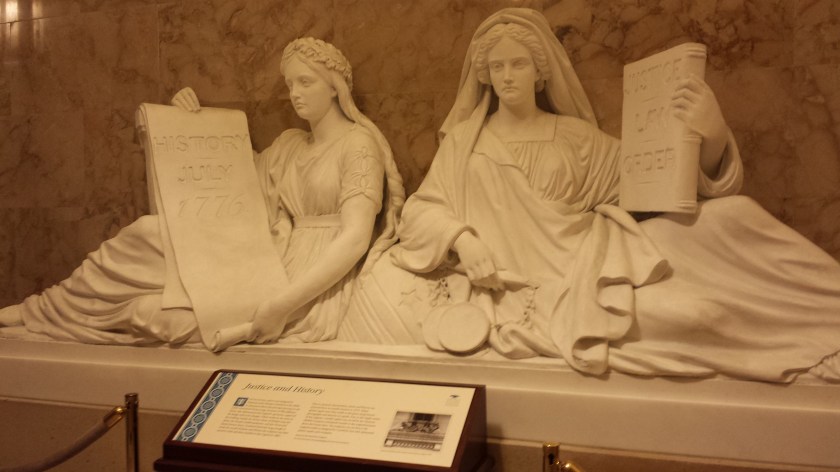

“I’ll just start by saying, Miss Greenway, that I don’t trust you.” The Chairperson sat behind a microphone on the curved oak desk in the Tribal Council chambers.

I stood in the center of a horseshoe circle of council members, many of whom burst into laughter upon hearing the Chairman’s statement. My knees literally shook as I realized just how unprepared I was to address the leaders of this Nation. I couldn’t wait to get back to Phoenix to let my boss know what I thought about him and his irrational idea.

Clearing my throat, I said, “I understand that…but frankly, I don’t trust you, either.” Where did that come from? I had no idea. It just leapt up into my throat and I let it fly! It would be over in a blink. But then the room erupted in laughter and even the stern face of the Chairman broke into a grin.

Most of the council members were large, heavy-framed men and women, with countenances that did not inspire casual conversation. Their laughter did not alleviate the tension for me. It only confused my thinking more.

“Well, now that that’s settled, maybe you can tell us why you are here.” The Chairman was extending me another chance.

Had I passed a test?

I followed with a lame description of the project I no longer believed in after my long meeting with Bill Sherwood. The Council, to their credit, listened without interruption or any indication of how they felt about what I said.

“Well, I am sure our elders will tell you what they think,” the Chairman said flatly. “I wish you good luck.”

Then he addressed David Tejano, who was present in the public seating area. “Mr. Tejano, I trust you will direct Miss Greenway where to begin.”

And that was that. I left somewhat dumbfounded yet grateful I’d made it through. Nevertheless, I realized as I walked to my car that no commitment or comments as to its potential relevance were made about an environmental education project.

David said goodbye with the assurance he would be in touch, and I left with my history book about the River People to return to my motel room. I flopped into bed, weary from tension, and began to read an incredible story about America’s Nile culture.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a botanist who explains her knowledge of an indigenous worldview about plants with that of the western worldview. In that process, Kimmerer embeds whole Earth teaching along with botanical science. Here in this beautiful essay,

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a botanist who explains her knowledge of an indigenous worldview about plants with that of the western worldview. In that process, Kimmerer embeds whole Earth teaching along with botanical science. Here in this beautiful essay,